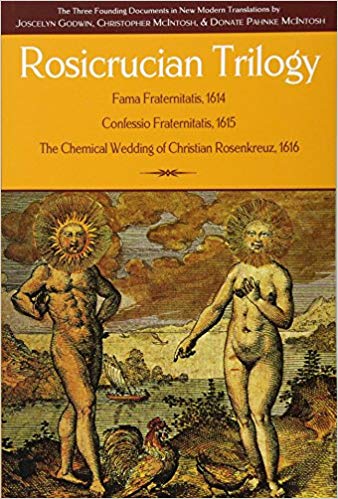

Rosicrucian Trilogy: Fama Fraternitatis, 1614; Confessio Fraternitatis, 1615; The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz, 1616

Trans. Joscelyn Godwin, Christopher McIntosh, and Donate Pahnke McIntosh

Weiser Books, 2016

184 pages

Paperback $22.95 USA, ISBN 978-1-57863-603-7

Hardcover $45 USA, ISBN 978-1-57863-609-9

The Rosicrucian movement began with three mysterious documents published in the early 17th century in Kessel, a city in the center of modern-day Germany. It was a movement that sprang from the Reformation, and it was steeped in esoteric lore, alchemical legends, and hope for a brighter and more rational future. The would-be Rosicrucians did not get their desired glorious future, however. The 17th century saw the eruption of the Thirty Years’ War and the death of millions through religious persecution, famine, and disease. However, the Rosicrucian legend survived and continues to have political and religious repercussions today.

Rosicrucian ideas have influenced Freemasonry in many ways, both overt and subtle. The Scottish Rite, for example, explores Rosicrucian concepts in its 18°, Knight Rose Croix. Similarly, the Societas Rosicruciana is active in most English-speaking Masonic jurisdictions and claims to be a Rosicrucian order. Even the Philalethes Society may have been influenced by a translation of the Rosicrucian manifestos. Historically, the Rosicrucian movement was beginning to gain speed as modern Freemasonry was taking form in the British Isles, which might further link the concepts and ideas of the Rosicrucian manifestos with Freemasonry. However, an exploration of the influence of Rosicrucianism on early Freemasonry is outside the scope of this book review.

Rosicrucian ideas have influenced Freemasonry in many ways, both overt and subtle. The Scottish Rite, for example, explores Rosicrucian concepts in its 18°, Knight Rose Croix. Similarly, the Societas Rosicruciana is active in most English-speaking Masonic jurisdictions and claims to be a Rosicrucian order. Even the Philalethes Society may have been influenced by a translation of the Rosicrucian manifestos. Historically, the Rosicrucian movement was beginning to gain speed as modern Freemasonry was taking form in the British Isles, which might further link the concepts and ideas of the Rosicrucian manifestos with Freemasonry. However, an exploration of the influence of Rosicrucianism on early Freemasonry is outside the scope of this book review.

The three Rosicrucian manifestos are the Fama Fraternitatis (1614), the Confessio Fraternitatis (1615), and The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreuz in the Year 1459 (1616). They were written by several men: Johann Valentin Andreae (1586-1654), a Protestant theologian; Tobias Hess (1558-1614), a Paracelsian physician; and Christoph Besold (1577-1638). The last English translation of the Fama and Confessio was in 1652, published under the pseudonym Eugenius Philalethes. A fresh, modern English translation has been badly needed.

The Fama Fraternitatis of 1614

This manifesto has been translated by Christopher McIntosh and Donate Pahnke McIntosh. Christopher McIntosh’s introduction provides valuable historical context that helps understand the desperate political and religious atmosphere of 17th century Germany. McIntosh also provides valuable historical background and brings attention to the sharp rise in millenarian beliefs, or beliefs that there was a coming transformation of society and the world through the return of Jesus Christ.

Taken in this context, the Fama is a fascinating read. The translators have provided a clear, understandable text that launches the reader into the esoteric Christian world of the Rosicrucian manifestos. This text presents a biography of a mysterious character referred to as “the pious, spiritual and highly illuminated pater, Fr. C.R.” This mysterious C.R. is eventually revealed to be Christian Rosenkreuz. It describes the structure of The Brethren of the Fraternity of the R.C. and then goes into great detail about the construction and nature of Christian Rosenkreuz’s tomb, a “vault of seven sides and corners.” This work refers to the Confessio, even though that manifesto probable hadn’t even been completed yet.

The Confessio Fraternitatis of 1615

Translated from the 1615 Latin edition by Joscelyn Godwin, this manifesto is interesting but not as purely entertaining as either the Fama or Chemical Wedding. The Confessio presents 37 arguments or reasons for the existence of the Rosicrucian brotherhood. These reasons are in fairly plain language, and are punctuated with little gems like referring to the Hapsburgs as “eagle feathers” and addressing its audience as “O Mortals.” The millenarian element is much stronger in this manifesto than in the Fama.

Godwin, well known for his many other translations and excellent works of Renaissance and esoteric studies, provides a useful and informative introduction. Probably the most helpful part of this introduction is a succinct breakdown and listing of the 37 arguments, because they are not clearly demarcated in the text.

The Fama continues to develop the Rosicrucian mythology with a symbolically rich esoteric Protestant Christianity. It mentions that the Rosicrucian fraternity, referred to as “the Brotherhood,” is divided into degrees (reason no. 12) and only available to those found worthy. Also, that the Brotherhood is intended to increase in size over time, and that membership is not hereditary, but conferred by merit alone. Deeply esoteric and spiritual, the close relationship between religion and Natural Science is evident in several places, such as by hinting that the Brotherhood understands heliocentrism and rejects “the vile books of the pseudo-chemists.”

The Chemical Wedding of 1616

Without a doubt, Godwin’s translation of Andreae’s Chymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosenkreutz anno Domini MCCCCLIX is the star of this book. This translation is based on Godwin’s previously published version in 1991. It is enhanced by numerous pen drawings by Hans Wilhelm Wildermann (1884-1954), which were first published in 1923. These whimsical illustrations add to the light-hearted character of The Chemical Wedding, which Godwin is quick to inform us was originally intended to be a satire.

Of the three manifestos, The Chemical Wedding is not only the longest, but the most esoteric. Godwin points out that Andreae must have been influenced by the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, and indeed it seems to have a similar structure. This manifesto is a first-person account by Christian Rosenkreuz of his journey through a fantastical land to witness a mysterious wedding. His adventure is filled with mythological creatures, unexplained symbolism, and curious characters. While it lacks the intricacy and elegance of the Hypnerotomachia, the story eventually develops into a complex interplay of ritual, alchemy, and symbolism.

Interestingly, The Chemical Wedding is almost devoid of the esoteric Christianity present in the Fama and Confessio. Instead, strong pagan themes are present, with both Cupid and Venus making strong appearances. Godwin explains in the introduction that the name Christian Rosenkreutz is actually based on the Andreae family crest, and may not be as loaded with overt Christian references as it seems to be.

Overall Impression

The scholarship of Christopher McIntosh and Joscelyn Godwin in their respective introductions is to be commended. The historical context and additional information they provide add a richness and cultural perspective to the manifestos that allows the reader to understand their role and importance in Western society.

This book is not large, but it is a fascinating read. It brings to mind many questions about the connection between the origins of modern Freemasonry and the birth of the Rosicrucian movement. On that basis alone, it is a recommended addition to any Masonic library and belongs on your reading list.

An earlier version of this review was published in Vol. 69, №4 (Fall 2016) of Philalethes: The Journal of Masonic Research & Letters.

Support my work on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/arnemancy

[…] The Rosicrucian Trilogy (also check out my review of this book) […]