This essay is a meditation stemming from visits to three shops in San Francisco, all of which provide items and services that can be utilized in spiritual systems, especially in alternative and non-mainstream beliefs. The three stores include a botánica (Tres Niñas Blancas in the Mission), an importer (The African Outlet in the Bayview), and an occult shop (The Sword and Rose in Cole Valley). These are merely local examples; you can find your own version of this story in your own town. The reasons why people frequent shops like these, and the functions these shops serve in their community, highlight changes on the spiritual landscape, which are worth exploring, namely:

- Spiritual trends have changed, in that “solo practitioners” and non-affiliated persons have set aside the traditional belief that spirituality can only be achieved within a group, such as at a mainstream church or temple.

- Dispersed “micro-minority” belief systems can connect in non-conventional ways, of course online via the internet, but also in real life (IRL) and in-person at shops like the ones discussed here.

- Spirituality or personal meaning can be found without a group. An individual, as a “solo practitioner,” is free to forge their own path.

- Certain spirituality shops or botánicas serve a function in the community that was once exclusive only to churches or organized religious centers.

- The question might be raised then: If spirituality is becoming more of an independent, solo experience, then should churches still receive the same benefits (and tax breaks) as in years past?

Going It Alone

For many, Spirituality or personal meaning is found outside of a traditional church or temple. The rise of the “Nones,” which includes people who identify as Non-Affiliated or Non-Religious, has been well-documented. Declining church numbers is part of a larger structural change—even social clubs and fraternities have also seen their numbers plummet as people choose different ways of engaging and socializing. Nones include those who say they are “spiritual but not religious,” those who are non-traditional in their beliefs, and those who simply prefer to be an independent Seeker, walking their own path independently, apart from a group.

Several New Religious Movements and spiritual systems on the periphery of the mainstream emphasize individuality more so than a group dynamic. For example, some Wiccan or magick systems meet in a group only irregularly, if at all, while many members might even identify as solo practitioners.

While Christianity has been the dominant belief system in the US for many centuries, even within the mainstream Christian context, there are many faithful who choose not to go to church, preferring instead to worship solo at home, independent of the group, through personal prayer or through their personal conduct.

Regardless of one’s beliefs, the coronavirus pandemic was a reminder that each of us has the power to direct our own spirituality, because when many churches were closed for months by public health order, the religious were left to connect with the Divine independently and without the comfort of the congregation, whether this was through prayer, study, or Zoom.

A Safe Place for Minority Voices

Spirituality shops not only serve as a resource for individuals, but also function as a brick-and-mortar meeting place for minority religions and belief systems which don’t have an adequate congregation size to build their own house of worship. For example, somebody identifying with Palo or Yoruba will be hard-pressed to find a congregation or temple for either religion in most American towns, but they might, however, find books or sacred objects for both faiths at their local occult shop or botánica. In that sense, spirituality shops and botánicas are like de facto, multifaceted temples of the mind, a functioning meetinghouse for minority faith groups.

What does one find inside these shops? The products and wares can reflect diverse cultures and minority religions including folk beliefs, Santeria, Yoruba, Palo, indigenious religions, animism, paganism, Afro-Cuban syncretized systems, Wicca, witchcraft, and even the more familiar major religions, including Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Catholicism, and Christianity.

Additionally, one finds examples of alternate beliefs which may fall just outside of the umbrella of religion, depending on who you ask, including magic, mysticism, New Age, and divination systems such as astrology, runes, and tarot. Overall, one could say these shops offer an alternative to mainstream beliefs, sometimes blended or syncretized.

“I’m Catholic,” says Luis Vasquez, the co-owner of Tres Niñas Blancas botánica. “To me, all religion is energy. The people who come here feel that energy from the shop, similar to a temple. This shop is not just a place to sell candles. Sometimes people just want to talk with somebody, in a safe place.” His shop’s diverse products demonstrate the unique syncretism of spirituality and religion, sometimes blending mainstream Christian or Catholic beliefs with ideas and practices from various cultures or religions.

Outside of these San Francisco examples, some shops have even clearly made the leap from commercial to spiritual. Some shops double as Santa Muerte churches in Las Vegas and Los Angeles, where the Templo Santa Muerte hosts a priest, podcast, and streams worship services.

This raises the question of what it means to be a religious organization, and demonstrates that some people come to shops like these for religious meaning that others find in a church. However, a church is sanctioned by the State with tax breaks and benefits, while a spirituality shop might be “othered”—labeled as magic, superstition, or “for entertainment purposes only,” just as certain fortune tellers are required to state in their advertisements. Imagine what clamor would arise if a mainstream evangelical church was required to advertise that their service was “for entertainment purposes only.” Yet, as a society, we clearly differentiate and segregate the two types of places.

Centers for Community

Spirituality shops can function as centers for their communities. Patrons do more here than simply buy or consume; they come to these shops to hang out, chat, cry, ask about their future or tell their secrets, share a meal and break bread. When people talk and learn from one another, they are exchanging ideas, building a narrative, nourishing relationships, or forging an anchor in the community.

Tres Niñas Blancas botánica visibly serves the marginalized and those on the periphery, including those from the migrant community and native Spanish-speakers, and members of the LGBTQ community. One NY Times article about the Santa Muerte movement suggests that members of the LGBTQ community in particular have found solace and identity with such non-traditional belief systems found at botánicas.

The botánica serves as more than a shop; it functions as a center of community. For example, the shop owners at Tres Niñas Blancas, Luis Vasquez and Mercredes Martinez, offer thoughtful blessings, limpias or cleansings, and annually on the Dia de los Muertos in November, they even hold a group rosary dedicated to the Santa Muerte. This prayer service certainly resembles a traditional religious experience: The faithful respectfully file in to the shop’s main room and sit upright at rows of chairs, in-line like church pews, the group prays aloud together, following the words of a rededicated rosary, and with incense and candles lit, the room is set for a mood of reverence and communion with the mystical.

“People here from other countries come to see the altar, to see the Saint, or to make an offering,” says Vasquez. His shop’s altars are reverently set apart from the products for sale, a line is delineated between the sacred and mundane. The large statues of the Santa Muerte are lovingly cared for like any other saint at a church, and especially on an occasion such as the Dia de los Muertos, when the statues are lavishly adorned with ornate gowns, the altars blanketed with fresh marigold blossoms.

The African Outlet is at Third Street & Quesada Ave in the Bayview. This neighborhood has historically been a predominately African-American community, and looking up and down Third Street, one sees the red, black, and green colors of the Pan-African flag proudly painted on dozens of lampposts. Inside The African Outlet, you can find a cornucopia of fetish statues and handmade religious relics from markets in West Africa. The shop owners, Judah Dwyer and Horgan Edet, met in 1987. Horgan is originally from Nigeria, and since the couple opened their first shop in San Francisco in 1989, they have brought much energy to their community. They have been longtime supporters of local dance and culture through their performance group, The African Outlet Experience, which has performed at the San Francisco Carnaval Parade, Juneteenth Parade, and celebrations of Black History Month and Kwanzaa.

Dwyer sees her shop as a resource in the community, a peaceful place that “provides grounding, inspiration, and another perspective.” Neighbors stop by for a chat or to break bread together, sharing a meal, not necessarily to purchase something. “We have food, we laugh. People drop in and hang out, exchange knowledge,” she explains.

In another neighborhood of San Francisco, Cole Valley, The Sword and Rose is a self-described “occult shop.” Shop owner Patrick Micheal points out that while occult means “hidden from view,” he does not associate the word occult with “darkness.” Rather, he sees his shop as helping people on their own individual journey, to learn what was otherwise unknown about themselves. “We offer people an inner spiritual compass, to find the way and the path that feels right to themselves.”

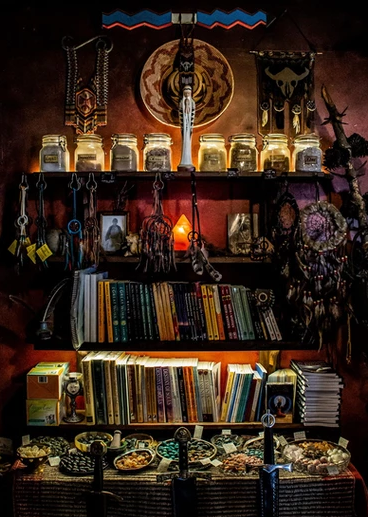

Stepping inside the small shop at The Sword and Rose, one finds a unique sensory experience. The interior is blanketed with treasures and curiosities to indulge a wandering eye, the lighting is low, and incense and perfume permeate the air. The attendants prepare custom incense concoctions for each patron, consecrated to a specific deity or spirit, and listen intently to personal woes or worries. A tarot reader conducts readings in a corner. Through these rituals in the shop, people are also sharing their secrets and wishes while trying to manifest desires or goals. Relationships are kindled and people seem to find the solace or fortitude they seek. This serves the same place in the community that a temple or church might serve for others.

“We’ve said that The Sword and Rose is a temple first and a metaphysical shop second,” says Teena from The Sword and Rose team. “I don’t know if we’re big enough to be labeled a community center, but would for sure agree it is a spiritual one. We are big in presence. People from all over make sure to come visit us or connect to us, from long time customers and friends to new ones. Our connections reach far and wide.”

“The Idol Shop”

Why would spirituality shops feel any pushback or discrimination? After all, they offer some of the same benefits and services as a church or community center. The answer is that a mainstream Christian culture can decide what is legitimate religion, and relegate to the heap of superstition or quackery anything which it deems to be hooey or unsavory. The word “magic” (or “idolatry,” for that matter) has been used to “other” those with divergent views from one’s own, according to Dr. Justin Sledge. What one person labels sorcery or trickery, another might label a miracle, and vice versa.

“I’ve seen people who pass by our store, cross to the other side of the street, and make the sign of the cross,” said Judah Dwyer of The African Outlet. “If people are ignorant of our shop, they might call it a ‘voodoo shop.’ Their friends taunt them to come in, then when they do come in, they’re surprised.”

“Some people are ignorant, and say this is the Devil,” Luis Vasquez says in a similar experience at his botánica, where statues of the Santa Muerte are proudly displayed in the window facing the public sidewalk. Vasquez takes a respectful approach to critics, responding, “It’s okay, I respect that, and I take my time with people. God is the only person who will judge us.”

An especially insightful story about the sentiment of critics of these shops can be found in the Midrash, a mystical commentary on the Hebrew Bible. It is said that Abraham’s father Terah operated a so-called, “idol shop.” To the chagrin of Abraham, the eponymous father of the Abrahamic religions and monotheism, his pop was a proud polytheist, and he carved and sold idols and statues of deities to customers looking for a custom Creator.

Abraham took an axe to his father’s wares, and like a bull in a china shop, Abraham smashed up his father’s idols. When Terah confronted his son about what he had done, Abraham blamed one of the idol statues for the destruction. Terah scoffed and said that was impossible because the idols had no real power, which was the perfect “gotcha” moment for Abraham, who exclaimed that worshiping and praying to these idols was futile.

This story is perhaps a metaphor for the violence that established religions have been willing to unleash on the minority faiths that posed uneasy questions. That is to say, in the story of Abraham’s axe-wielding rage inside the idol shop, we see an historical analogy for how monotheism dealt a crushing blow to its polytheistic precedents, when, over the centuries, organized religion flexed its dominance over individuality and personal spirituality. One wonders about this story from the point of view of the idol shop’s owner and patrons; perhaps the place was actually a beloved center of the community, and provided tools for individual contemplation for solo practitioners. “History is written by the victors,” says the famous maxim, and perhaps likewise we’ll never know how many countless so-called “idol shops” which were smashed up or buried beneath a temple or church, swept away and forgotten.

Of One and Many

Austin Osman Spare created an entire religion for which he was the lone believer, the Zos Kia Cultus, and he made this in his room, complete with deities and rituals—a solo psychonaut travelling on his own astral plane. But despite creating a complex belief system with no other practitioners, Zos Kia Cultus might be better characterized as one man’s worldview, rather than a bona fide religion.

Must spirituality or religiosity even be put on a pedestal above philosophical inquiry and study? If an individual is well-read and well-versed in the words of Plato, Marcus Aurelius, or Schopenhauer, and they conduct their life in a disciplined and virtuous manner, but they don’t identify as religious or spiritual, and never go to church, then was this work all for naught? One would hope not. Sunday schools don’t often emphasize that religiosity and ethics are two different matters, and there are many examples of religious people who have committed heinous acts, or non-religious people who exemplify noble deeds.

The question can be raised then, why are churches and religious centers given tax breaks and benefits, under the assumption that their works enrich the community in some unique way?

Must we practice spirituality with a group for our beliefs to matter? According to some, “yes,” and there are numerous benefits to ditching the solo path for the road well-travelled.

A group may be stronger than the sum of its parts, and it has been suggested that a kind of “group magic” might bring about a secondary force, dynamic, or egregore. The Gospel of Matthew states that, “For where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them,” as if group prayer conjures a secondary presence. The mystical book Tanya credits group prayer as being so powerful that, when a congregation gathers to pray, an angel passing above might be instantly nullified, as if hit by an energy beam. Groups offer a vibe not possible alone, groups offer an exchange of ideas, mentorship and guidance, and a sense of belonging and community.

“We’re not a faith center,” Judith Dwyer distinguishes The African Outlet from shops which blur the line between shop and church. “We’re not proponents of that approach. Organized religions have destroyed indigenous cultures.” Dwyer seems to extol the value of individuals and minority beliefs holding steadfast against the mainstream, against religions which historically have been, “conquerors.”

Solo practitioners, it seems, have the benefit of quietly finding their center at their own pace, in calm solitude and meditation. Without interference, the solo practitioner can focus on core values, and hone their skill or study. Even Jesus seemed to advocate for some solo time, saying of prayer, “when thou prayest, enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret.” Mysticism is most valuable when one has an individual connection to the Divine, something that can only be attained on a personal level, not necessarily within a crowded cathedral, but simply in the mind, according to William James in his opus The Varieties of Religious Experience.

But group dynamism and the label “church” is still so evasive and powerful, that even atheists, when working within the modality of a church-going culture, have founded atheist churches, both to make a point, and in a nod to a shifting spiritual landscape. The Harvard Divinity School even offers chaplaincies for those who identify as atheist, agnostic, or humanist. The Satanic Temple, which has made some notable public spectacles and lawsuits to advocate for the separation of church and state, is professedly non-theistic (and they say they don’t literally believe in their eponymous deity), but the group seems to see value in the label and legal status of being a “church.” What does this tell us about the power of the word “church,” when even non-religious people who might prefer to philosophize individually, find it necessary to congregate as a church?

Friends with Benefits

While churches and organized mainstream religions have seen falling attendance in recent decades, having lost touch with their flock, or not kept up with changing needs and trends, still though, they receive generous financial benefits and tax breaks not afforded to individual seekers or non-traditional spiritual centers like shops or botánicas.

The image of a humble church on a town square might elicit sympathy for shelter and tax breaks, and perhaps small congregations should receive legal protections. To be clear, many churches do pay some taxes, such as property tax, and the staff may pay personal income tax. And most non-profit organizations, including non-religious ones, have similar protections.

Yet, the church tax break has been famously exploited as a loophole. Dozens of sleazy televangelists zip around on private jets while asking their faithful for more handouts. Plenty of examples abound, so much so that one wonders if the tax exempt status of churches ought to be reconsidered. One especially wealthy church, fearing it would lose its tax exempt status, even went so far as to burglarize the IRS, cloak-and-dagger style. The Twitter hashtag #TaxTheChurches continues to bubble in popularity. Some churches have amassed considerable fortunes, so much so that a 2020 Wall Street Journal investigative report found that the Mormon church had stockpiled a 100-billion dollar nest egg. The problem has been so pervasive, in fact, that even a Republican Senator, Chuck Grassley, whose party has long been affiliated with the Religious Right, launched a Congressional investigation into the tax exempt benefits of wealthy churches.

Here we have examples of non-profits that are in fact clearly very profitable. And perhaps this blurred line shouldn’t come as a surprise, when even famous for-profits can’t turn a profit. AirBnB, Pinterest, and Uber might have high stock valuations, but that’s based on hype, because these companies don’t make a dime of profit. This accentuates the question, what does it even mean to be a non-profit that’s profitable, or a for-profit that’s not profitable? Perhaps these definitions and loopholes should be reconsidered altogether.

Churches are obligated to remain non-political in order to keep their tax free status, but another line is crossed when many churches make bold political endorsements, both on the Left and Right. Many progressive churches are open about their political advocacy. And on the other end of the spectrum, in 2008, the Mormon church drew the ire of critics when they openly endorsed Prop 8 to stop gay marriage in California.

Is it possible that spirituality and religion can be pushed back to a place of individuality? Where groups pandering for converts are not given a monetary advantage over individuals or small shops? Is it fair that a group receives a break at all, when individual beliefs or micro-minority beliefs are left to flounder or sink without those same breaks and protections?

The Power of One

When we question what it means to be religious or spiritual, we find that spiritual beliefs can’t be fitted neatly in a box or affixed with a label, instead lines are blurred and contradictions are rampant. Entire temples or churches might be religious in name, but faithless in function, perhaps merely going through the motions on the major holidays. One could believe in spiritual concepts, such as reincarnation or astrology, without believing in an overarching deity. Spiritual matters then, like the rest of life, are messy and complicated.

Each of the major religions started from humble beginnings, each movement was catalyzed by individual prophets, and the many started from one. That is, mass movements and today’s established systems each started from a single point: from a single book, the words of a single prophet, or a single event, and then multiplied, expanding outward like a fractal. Likewise, the radical notion that individuals have the ability to read and make up their own mind, independent of clergy, empowered Martin Luther’s Reformation, and viralized the popularity of Gutenberg’s printing press. That same power to reform, reinvigorate, or create, is not confined to ancient history, but rather, fresh ideation and individual interpretation are renewed and available today and tomorrow.

Each person, then, would seem to have the power to be their own maggid, storyteller, leader, or prophet. We can each forge our own path, cherry pick from the great spiritual systems, haggle in the marketplace of ideas, and interpret or rearrange ideas as we see fit and as we wish. This process is the same as every other religion or prophet has done for thousands of years, whether or not they’re willing to acknowledge their messy history of cross-cultural mixing and appropriations. Call this an acknowledgment of the reality of spiritual anarchy.

More Reading

For an in-depth exploration of some of the themes in this essay, and for a history of botánicas in particular, check out Botánicas: Sacred Spaces of Healing and Devotion of Urban America, by Georgetown professor Joseph M. Murphy.

Tony Gilbert is a freelance writer in San Francisco, California. He is searching for a publisher for his manuscript novel titled “The Egregore,” about icons and botanicas in San Francisco’s Mission District. See the book’s preview here.

Leave a Reply