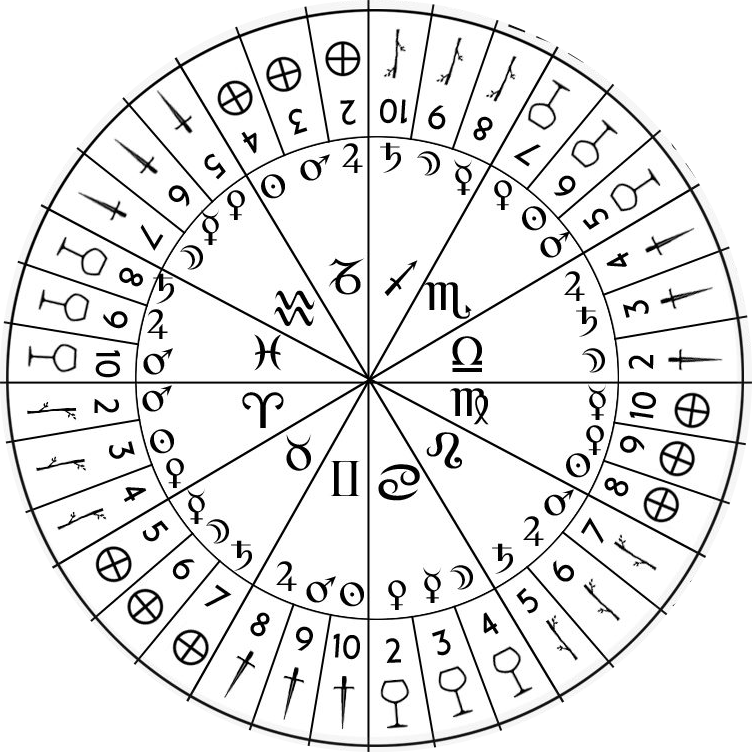

The terms “decan” and “face” are often used synonymously in astrology: a 10° division of the 30° covered by a sign of the Zodiac. In other words, each sign contains three decans, or faces. While each sign has specific relationships with the various planets, each decan does as well. Each decan is said to have a specific planet as its ruler. Usually the rulers of the decans are not obviously related to the rulers of the signs.

Planetary rulerships of the decans are assigned sequentially, beginning with the first decan of Aries, which runs from 0° through 9°, and is ruled by Mars. The second decan of Aries, 10° through 19°, is ruled by the Sun, and Venus rules the third. Rulership continues in Chaldean order, which is the order that the planetary spheres are placed in your standard classical Ptolemaic cosmos.

- Saturn

- Jupiter

- Mars (start here for decans!)

- The Sun

- Venus

- Mercury

- The Moon

Though Mars rules Aries and his first decan is ruled by Mars, it doesn’t work out that logically for the rest of the signs. This is reflected in the interpretations of the decans and how they are used both in divinatory astrology and astrological magic. For an example of how the decans are used in astrological divination, check out Andrew B. Watt’s Decans column.

The astrological signs and the planetary rulerships of the decans, along with Tarot correspondences. This image was created by T. Susan Chang and used with her permission.

For astrological magic, each of the 36 decans are given magical images. These are found in a number of classical sources, including one of my favorites, the Picatrix. The Picatrix presents multiple sets of magical images for the decans, and for this particular article, we’ll be looking at the images presented in book 2, chapter 11. These images are striking and sometimes shocking, just as good magical images should be.

Tarot Decans

Interestingly, modern Tarot (i.e. Tarot since the 19th century) also presents images for the 36 decans. You can find these images by understanding the correspondences between the Minor Arcana and the decans. If you take the subset of 2 through 10 of each suite, you end up with 36 cards. Somebody, possibly a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, attributed these 36 cards to the 36 decans, which means that the images associated with these cards can also be paired with the decans.

The cards are assigned to the decans by both number and the elemental correspondence of their suits. Since not all decks use the same set of elemental correspondences, for this method we need to use the same associations used by the Golden Dawn: Wands are Fire, Cups are Water, Swords are Air, and Pentacles are Earth. In each suit, the 2, 3, and 4 are assigned to the decans of its element’s cardinal sign. The 5, 6, and 7 are assigned to the fixed sign, and the 8, 9, and 10 are assigned to the mutable sign. For example, the following table lists the decan associations for the Cups.

| ♋ Cancer | Cardinal Water | 2, 3, 4 of Cups |

| ♏ Scorpio | Fixed Water | 5, 6, 7 of Cups |

| ♓ Pisces | Mutable Water | 8, 9, 10 of Cups |

As an added bonus, this method gives each of these Minor Arcana cards both a planet and sign correspondence. With just a little extra work, this can be used as a Tarot mnemonic. For a thorough discussion of how Tarot corresponds with the decans and other astrological topics, I recommend Tarot Correspondences: Ancient Secrets for Everyday Readers by T. Susan Chang.1

Meeting the Picatrix Faces

Now that we have both a set of medieval images for the decans from the Picatrix, and a modern set of images from the Tarot, what can we learn by comparing the two? Are there any interesting parallels or shocking differences?

To answer these questions, I turned to the cards! Using J Swofford’s Picatrix Decans talisman deck, I randomly selected the faces of Virgo. Virgo is the mutable Earth sign, so its decans correspond to the 8, 9, and 10 of Pentacles. Comparing the Picatrix images to the images of the Waite-Smith Tarot, it’s easy to see that the images are strikingly different. It is difficult to draw any sweeping parallels between the two sets of images.

The three faces of Virgo from J Swofford’s Picatrix Decan images, alongside the 8, 9, and 10 of Pentacles from the Waite-Smith Tarot

Let us narrow our attention on just the first decan of Virgo, which is ruled by the Sun and is associated with the 8 of Pentacles. The Picatrix describes this image as “a virgin covered in an old, soft linen cloth, holding a pomegranate in her hand.”2 J has interpreted the virgin with the pomegranate as Persephone, and his depiction is rich with imagery of Hades, death, seasonal change, and growing plants. This fits well with what the Picatrix says about this image, which is that it is the face for “sowing, plowing, germinating trees, [and] collecting grapes.”3

When we turn to the 8 of Pentacles, however, we see something very different. A craftsman labors at his bench, working hard to finish another pentacle. The fruits of his labors surround him, mounted on the wall and leaning against his workbench. Connecting this imagery to that of the Picatrix face takes a lot of uncomfortable stretching. In fact, the 9 of Pentacles with its grapevines seemingly has more in common.

The 8 of Pentacles does show good honest work and toil as being the method to progress and overcome obstacles. There is nothing more earthy than physical labor. Along that same line, the first face of Virgo in the Picatrix speaks of that time of year when physical labor is needed in the fields and vineyards. This might be the thread of meaning connecting these two disparate systems of magical imagery.

Looking at the other two Tarot cards for Virgo’s decans, there are a few obvious similarities. For example, the third face of Virgo is about old age, which the 10 of Pentacles also refers to. However, the Picatrix image is about “weakness, old age, sickness, laziness, the cursing of body parts, and the destruction of people.”4 This does not jive with the peaceful, content, and prosperous old age of the 10 of Pentacles.

Bringing It Together

This is just a small sample of the decans, so it is hard to argue that it is representative of the differences between the Picatrix images and the minor arcana. It could be that a deeper examination will reveal a wealth of similarities, but I doubt it. The medieval Picatrix and the modern Golden Dawn Tarot represent two different approaches to a similar esoteric concept. The Golden Dawn burdened itself with wanting all occult philosophy and magical tradition to fit together into a nice, convenient (though crowded) package.

The Picatrix, on the other hand, is not afraid to present multiple systems and multiple approaches to the same topic, sometimes right on top of each other! The decans are a perfect example. We have been looking at the decans as presented in book 2, chapter 11. However, book 2, chapter 12 presents a whole different set of decan images and their interpretations!

What can we learn from this? I think the most important lesson is that we should beware dogma in the occult. Much of the systems presented by our predecessors needs to be sifted through, closely examined, and experienced by each individual practitioner. To understand the important part of a system takes trial, error, and experimentation.

If you would like to experiment for yourself with the decan images of the Picatrix, you can find J Swofford’s deck of all 36 Picatrix Decan talisman images in the Arnemancy Shop.

Did you like this article? My patrons received it five days early. Support my work on Patreon!

- You should also check out my interview with Susan on the Arnemancy Podcast! ↩

- Majrīṭī, Maslamah ibn Aḥmad. Picatrix: a medieval treatise on astral magic. Translated by Dan Attrell and David Porreca. Magic in History. University Park. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. 118 (2.11.18). ↩

- ibid. ↩

- ibid. 118 (2.11.20). ↩

Leave a Reply