Giordano Bruno (the Nolan) was an influential philosopher, astrologer, and poet who was burned at the stake for heresy in 1600 C.E. He was a loud, brash, opinionated ex-monk who was not shy about his support of heliocentrism and his rejection of Christianity. He was also a genius. Bruno’s place in the history of Western civilization got a big upgrade in 1964, when Frances Yates published Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition. That book was my first introduction to Bruno and his work.

I haven’t read much of Bruno’s work, but I’ve been studying the Art of Memory for a long time and was excited to read Bruno’s De Umbris Idearum: On the Shadows of Ideas, recently translated by Scott Gosnell. This book contains both De umbris idearum and Ars memoriae, which are Bruno’s work on the nature of ideas and imagination as well as his complex mnemonic system.

I haven’t read much of Bruno’s work, but I’ve been studying the Art of Memory for a long time and was excited to read Bruno’s De Umbris Idearum: On the Shadows of Ideas, recently translated by Scott Gosnell. This book contains both De umbris idearum and Ars memoriae, which are Bruno’s work on the nature of ideas and imagination as well as his complex mnemonic system.

Gosnell’s translation has received some flack in Amazon reviews. One reviewer writes, “If you want to understand what level this translation is at, then cut some Latin text and paste it into Google translate and you’ll get the idea.” That reviewer is being too hard on Gosnell. Bruno’s Latin is difficult, and nobody else has stepped forward to translate these texts into English. The original texts are available online for both De umbris idearum and Ars memoriae. I’ve experimented with pasting portions into Google Translate, and Gosnell’s translation is far more readable than the gibberish Google produces.

Bruno’s work is dense and difficult to decipher. Gosnell tries to help in a few places, but it will take a lot of study to decipher Bruno’s intent and figure out exactly how his version of the Art works. Bruno says that it will take months of practice, stating, “Within the space of three or perhaps four revolutions of the moon, you’ll get results; within six you should have mastery.”1 Since I just finished reading the book and have only started thinking about it, what follows are my initial notes. I hope that they are useful for others beginning to use the Nolan’s incredible art to improve their own memories and imaginations.

This article will focus on the second part of Gosnell’s translation, Bruno’s Ars memoriae.

Terminology

Bruno uses different terminology for several standard terms in the Art of Memory. While there aren’t many variations, this short table should be useful to keep all the differences straight.

| Classical | Bruno | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Locus | Subject | A scene or space in a memory palace. |

| Image | Adject | A memorable, striking image placed in a locus. |

Clavis Magna, or the Great Key

Forma vero extrinseca, atque figura inuentoris clauis magnæ; per artem duro committitur lapidi, vel adamanti.

Actual external forms, as in the figure of intentions from the Clavis Magna, are as difficult to make as a stone such as a diamond.2

Throughout Ars memoriae, Bruno references something that might be an external work, the Clavis Magna. He never makes it clear if this is another book. Gosnell speculates that it may be the result of committing Bruno’s entire work to memory. It may also be a work that Bruno never published, or one of his other works on memory, such as the Cantus Circaeus.

Rules for Subjects

Bruno doesn’t have very many rules for subjects, or loci, that would be surprising to somebody who’s already studied the Art of Memory. He records many of the standard pieces of advice. For example, he notes that “a healthy image derives from a happy and noble subject” and that this is something which each practitioner will need to figure out with his own experience.3

Photo by Ed Uthman on Flickr.

If a subject is difficult to recall clearly, Bruno suggests adding or subtracting elements from it. For instance, subtracting elements would be like carving a statue of Mercury from a stone. Or, as he puts it: “Subtractione, ex lapide fit Mercurius.”5 That particular piece of advice, though a lovely quote, seems like it would make a subject more complicated and difficult to recall. It will take experimentation.

Finally, Bruno recommends repeated, daily practice. The memory palace should be walked daily. And the student should not be afraid to change his subjects over time, as “that which is uniform and undifferentiated generates revulsion.” Bruno also states that imaginary architecture should work just as well as real architecture, which is not typical advice for loci.6

Rules for Adjects

It’s going to be difficult to summarize Bruno’s rules for adjects. He breezes through subjects. Ars memoriae is primarily an instruction manual for the creation of adjects. Bruno’s adjects and subjects follow many of the same rules. The main difference seems to be that while subjects are reused in a fixed order, the adjects placed in them are reused in different combinations.7 Adjects are a complex visual alphabet, and as such they do not need to be attached to subjects to be useful. Instead, adjects are placed with subjects when order is important.

Subjects and adjects should be related. For instance, if the student chooses to use Bruno’s example adjects based on Greek mythology, the subjects should be Greek architecture. If the student chooses to use the Knights of the Round Table instead, then the subjects should be based on Camelot.8

Intention arouses the imagination. Adjects should be created purposefully so that they are easier to visualize and form.9 Bruno states that images should be created with discretion, determination, and ordination. He gives some additional advice.

- The memory system is like a canvas, and the student’s imagination is like a painter.

- Keeping things in order (ordination) keeps them from being confused.

- Order also keeps your adjects indexed. When information is kept in order, it’s easier to find.10

Bruno’s adjects are also endowed with movement. This is because movement brings objects to life. According to Hermetic philosophy, anything with movement is endowed with soul, which makes it part of the soul of the cosmos.11

Wheels of Adjects

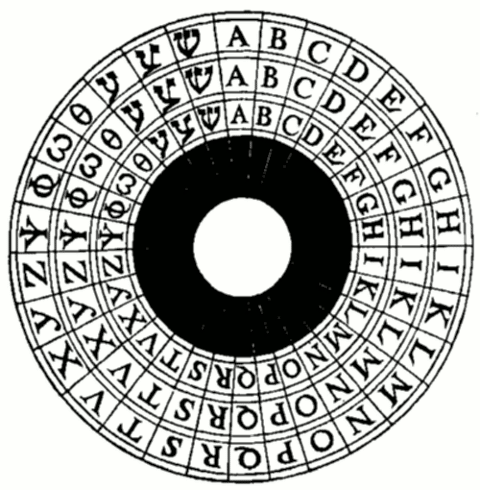

After explaining the rules for adjects, Bruno presents a comprehensive system for creating adjects quickly. His system uses a visual alphabet with layers of symbols that can be used to recall entire words. It is a complicated take on a Person-Action-Object (PAO) system, which this short article won’t explain in great detail.

These memory wheels are used to build images up to five layers deep, which means a library of 24,300,000 adjects can be created with Bruno’s 30-space memory wheel, pictured above. It’s an interesting system. Bruno’s method for learning encourages the student to build it up slowly, with just one or two layers at first, and to increase over time. The last part of Ars memoriae is a catalog of sample memory systems based on various mythological and astrological sources. I get the impression that Bruno is suggesting that the student build his own catalog.

Conclusion

As I mentioned earlier, these are just the notes that I made while going through Bruno’s system for the first time. I look forward to hearing your thoughts about Bruno’s system. What is your experience with it? Was the Nolan a genius, or a mad genius?

Did you like this article? My patrons received new articles five days early. Support my work on Patreon!

Gosnell, p. 79. ↩

Page 63. Emphasis in the Latin is mine. ↩

Page 73. ↩

Page 75. ↩

Page 77. ↩

Page 69. ↩

Page 88. ↩

Page 86. The Camelot example is mine, so don’t get too excited. ↩

Page 89. ↩

Page 91. ↩

Farinella, Alessandro G., and Carole Preston. 2002. “Giordano Bruno: Neoplatonism and the Wheel of Memory in the “de Umbris Idearum””. Renaissance Quarterly 55 (2). [University of Chicago Press, Renaissance Society of America]: 596–624. doi:10.2307/1262319. ↩

It is humbling to consider the Platonic dialogues and to notice that some, if not all, are all based on one of the characters memory. Implying to me a previous oral tradition which began to be written. One in particular, The Parmenides, one that seems fits the model for Bruno. Studying Pierre Grimes Phd. work he lays out quite well the structure of the dialectic and binds it with the concepts of analogy and the make up of a 3 and 4 term analogies. Quite fascinating and of which the Parmenides is a ‘go to’ for such a structure. Such a seemingly daunting task made easier by use of its structure as in the article above and as Bruno has written.

I have not read the Parmenides, but in Phaedrus, Socrates recounts an old Egyptian tale about the importance of memory: “And in this instance, you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a quality which they cannot have; for this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves.”

The Art of Memory that Bruno’s work is based on was supposedly invented by Simonides, who lived in the 6th-5th c. BCE. I will read the Parmenides and check out Pierre Grimes’ work. Thanks!

Wonderful quote from the Phaedrus, thank you. I had forgotten that. Pierre has a wonderful video on YouTube on the Phaedrus ” Out of body experience in the Phaedrus” . will post a link when I get a chance.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5E3zTL25QGg&list=FLkSYwFTVwb7O67Y2Zwds9gQ&index=13

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ztrbJjlYdi8&list=FLkSYwFTVwb7O67Y2Zwds9gQ&index=11 not sure how it posted a martial art video..wacky.

Yeah, weird! Well, that’s a long video, so I’ll have to watch it later when I have time.

[…] with Giordano Bruno’s memory alphabet and wheel system opens up interesting possibilities. I’ve written before about using tarot […]

[…] Mere rote memorization of the cards just gets you numbers and keywords, while using the Art of Memory gets you the entire experience of seeing, recalling, and using the […]

[…] addition, I would recommend reading my other articles on this site, Giordano Bruno’s Art of Memory and The Tarot Memory […]

[…] https://arnemancy.com/articles/art-of-memory/giordano-brunos-art-of-memory/ […]

Hey there

How would you use this wheel to memorize a Masonic ritual?

Well, that’s a complicated question. First, I have a Masonic memory alphabet that I’ve created. So I’d use that. Next, it depends how comfortable I am with the ritual. Does it need to be word perfect, for instance? Do I just need help remembering specific letters?

As you begin to study the ritual, you will notice that your first memory palace has already been constructed. It stands waiting for you, along with a series of objects to observe and comment on as you walk through.

[…] https://arnemancy.com/articles/art-of-memory/giordano-brunos-art-of-memory/ […]

[…] Gosnell joins me for an amazing conversation about Giordano Bruno‘s work, in particular On Magic and Thirty Statues, which he just finished translating and […]

[…] https://arnemancy.com/articles/art-of-memory/giordano-brunos-art-of-memory/ […]

[…] of the techniques of the Art uses visually stimulating images to aid recall. Using imagery to store and recall information was common in Europe before the general availability […]

[…] Reverend Erik has written about the Art of Memory, which uses similar systems to contextualize and relate information, directed at better recall. […]